“Jigane” (base metal) refers to the fundamental metal materials used in traditional crafts and metalworking before decoration or processing is applied. The type and quality of jigane significantly impact the beauty and strength of the final piece, making it an extremely important element for craftsmen.

In this article, we will clearly explain the basic meaning and characteristics of jigane, how it is used in traditional crafts, and its role in creating masterpieces. Please read on to gain foundational knowledge that will help you understand the deeper appeal of traditional crafts.

Table of Contents

What is Jigane? Understanding Its Meaning and Role in Traditional Crafts

When you hear “jigane,” many people might think of the financial and investment world, but in traditional crafts, it has a completely different meaning. Here, we’ll accurately understand the definition of “jigane” in crafts, organize the characteristics of “metal materials” that form the foundation of works, and their importance in production.

Furthermore, we’ll touch on the differences from wood base (kiji) and raw material (soji), as well as the processing suitability and expression differences of each material, clarifying how jigane influences the appeal of works.

How Does It Differ from Financial “Jigane”? – Definition in Crafts

While “jigane” in finance evokes thoughts of high-purity precious metal ingots and bullion trading of gold, silver, and platinum, jigane in crafts is somewhat different. In the craft field, “jigane” refers to the metal materials themselves that form the foundation of works, used in casting, forging, and metal engraving processes.

This is simply a term referring to materials, and how jigane is handled greatly affects the expression and texture of the work. For example, jigane used in casting changes surface texture depending on viscosity and cooling speed when melted and poured into molds, while forging creates unique lines and shadows characteristic of hammering plate-shaped jigane into form.

In other words, jigane is the skeleton of the work, serving as the “foundation” while playing a major role in influencing the final impression.

Differences from Wood Base and Raw Material – The Concept of “Metal Foundation” Supporting Works

While wood base (kiji) and raw material (soji) refer to the simple state of form and surface of works, jigane is a similar concept for metal products. If wood base is the raw material after shaping wood, jigane refers to the basic process of preparing metal materials into forms suitable for molds and manufacturing methods.

In casting, first the jigane is melted and poured into molds, called “casting jigane,” while in forging and raising, the metal plates for hammering and stretching are called jigane. The process of shaping jigane requires processing methods that consider the unique flexibility, strength, and surface texture of the material, and the quality here greatly affects the durability and texture of the work.

Just as raw materials are polished and finished, the state of jigane directly connects to subsequent finishing, making it extremely important as the “metal foundation.”

Gold, Silver, Copper, Iron… Different Processing Suitability and Expression by Material

Each metal has different properties and creates significant differences in craft expression. Gold is soft with excellent malleability, suitable for decoration and detailed work as it can be processed into extremely thin sheets like gold leaf. Silver is widely used in silverware and metal engraving, while its oxidation properties that cause blackening are also utilized for aged appearances.

Copper is suitable for casting, with beautiful rust (verdigris) and color changes from heat treatment being highly valued, used in traditional crafts like Takaoka copperware. Iron is suitable for forging, with its strength utilized in armor, tools, and pots.

Furthermore, in processes like mokume-gane that layer multiple metals to create patterns, beautiful designs emerge from material differences. These material differences become the properties of the jigane itself used in metalworking, deeply affecting the completeness and appeal of craft works.

“Jigane” is an important concept forming the foundation of metal crafts. While often confused with financial terms, in crafts it plays a major role as the material foundation, affecting expression and strength during processing. Understanding the differences from wood base and raw materials, and knowing the processing suitability of each material, should help you appreciate the depth of metal crafts.

The History of Jigane Supporting Japanese Crafts

Jigane symbolizes both the presence of materials themselves and the evolution of technology in Japanese metalworking. From forged iron of the Kofun period, to beauty as objects of appreciation in tea ceremony, to brilliant success at international expositions in the Meiji era, jigane has walked through history alongside crafts.

Below, we’ll unravel this flow through three historical periods, explaining how jigane became the foundation of Japanese crafts.

Jigane Metal Culture Beginning with Kofun Period Forged Iron

The origin of Japan’s jigane culture is considered to be the forged iron technology that began in the Kofun period. From the 6th century onward, the “tatara ironmaking” technique spread throughout the country, involving alternately adding iron sand and charcoal to clay furnaces while sending air with bellows (fuigo). For example, box-shaped furnaces have been confirmed in Hiroshima and Okayama, and iron arrowheads and ceremonial iron products have been excavated from ironmaking facilities of that time.

Tatara ironmaking was an advanced process requiring understanding of material composition and processing methods for steel production, laying the foundation for jigane used not only in agricultural tools and weapons, but later in tea ceremony utensils and cast products. The production methods for tamahagane (jewel steel) that continue today were already uniquely developed in Japan by the late 7th century, suggesting that traditional technical systems were formed alongside jigane.

The Beauty of Jigane Refined by Tea Ceremony – Rikyu-Style Kettles and Iron Flower Vases

Throughout the Momoyama and Edo periods, tea masters like Sen no Rikyu and Kobori Enshu focused on the beauty of jigane as tea ceremony utensils. Particularly, iron “Rikyu kettles” were masterpieces combining materials obtained from tatara ironmaking with casting technology, where the texture of cast surfaces and blackness harmonized with steam from boiling water, considered the “ultimate expression of wabi” where utility and beauty merged.

Iron flower vases also became popular as tools that enhanced the spirituality of tea ceremony, as their material texture blended well with tea rooms. These items were appreciated as art not only for their shape and dimensions, but also including the feel, sound, and color changes of the tools used, representing an important turning point that gave jigane “beauty beyond its foundation role.”

These tea ceremony utensils were appreciated including not only form and dimensions but also the feel of jigane, the sound when boiling water, and the colors that change over time, representing a turning point that gave iron, which had been merely “material,” artistic value as an “expressive medium reflecting wabi-sabi.” Even in modern tea ceremonies, the quiet black of Rikyu-style kettles and the profound texture of iron flower vases reflect deep wabi within simplicity.

Inlay, Cloisonné, and Ornamental Metalwork Triumphs That Amazed the World at Meiji Expositions

The Meiji government positioned international expositions as stages for “craft nation-building,” exhibiting extraordinary craftsmanship in inlay (zogan), cloisonné, and ornamental metalwork. At the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, three large bronzes displayed in the Japanese pavilion and exquisite inlay and metal engraving pieces were purchased by American business leaders and are still introduced as “amazing detailed sculptures” in the Driehaus Museum collection.

At the subsequent 1900 Paris Exposition, Namikawa Yasuyuki’s “Cloisonné Four Seasons Flowers and Birds Vase” won the gold medal, with French newspapers praising its “unprecedented precision.” At the same exposition, works by Kyoto inlay craftsmen including iron base gold and silver inlay plates also won awards, with Japanese ornamental metalwork highly praised as having “elevated metal to a decorative canvas.”

The geometric patterns depicted in inlay, the vivid colors emitted by cloisonné, and the delicate embossing of ornamental metalwork gave great shock to Western craft enthusiasts. These achievements overturned the concept of “jigane = mere material,” marking a turning point where Japanese metalwork was officially recognized as artistic works on the international stage.

Deep Dive by Technique! Three Major Processes Where Jigane Comes Alive

In metalworking, the appeal of jigane greatly depends on how the material is handled. What significantly affects the completeness of works are the forming processes of forging and casting, metal engraving techniques like chisel carving and inlay, and chemical coloring methods like shakudo and blackened copper.

Understanding these techniques reveals how jigane as a foundation is elevated to three-dimensional works and delicate patterns. Let’s explore in detail the three major processes that draw out jigane’s full potential.

Forging vs Casting – Differences in Form Created by “Hammering” and “Pouring”

Forging (tanzo) and casting (chuzo) are fundamental yet extremely different metalworking techniques. Forging is a method of shaping heated jigane by hammering or pressing, also used in metal forging and sword making. The hammering densifies the metal interior, improving strength while enabling smooth curved surfaces and plate-like formations.

Casting, on the other hand, involves melting jigane, pouring it into molds, and cooling to solidify. This method easily creates complex shapes and three-dimensional forms, widely used in cast Buddhist implements and decorative items, but tends to develop internal air bubbles called “blowholes” and generally has inferior strength compared to forged products. Forging tends to produce strength and forged luster, while casting excels at details and mass production. Craftsmen utilize each method’s characteristics, choosing based on purpose and artistic intent.

Chisel Carving, Inlay, Cut Gold – Metal Engraving Techniques That Bring Patterns to Life

Metal engraving techniques that carve jigane and bring patterns to life represent the essence of Japanese metalwork. Representative is chisel carving, which uses chisels (tagane) to carve into jigane, including various methods like “fine engraving” for thin lines, “kick engraving” for three-dimensional effects, and “single-sided engraving” for simply deepening one side. Inlay involves hammering gold, silver, copper and other materials into carved slopes to create patterns with different materials, with various types including “line inlay,” “flat inlay,” “textile inlay,” and “high relief inlay.” Particularly, textile inlay is an advanced technique requiring carving minute grooves, beautifully expressing diverse metal patterns with fine silk-like texture. These metal engraving techniques are supported by skilled craftsmanship including blade selection, carving strength variation, and hammering pressure, with the patterns emerging from jigane themselves elevated to “jigane expression.”

Reference: Introduction to Living National Treasure Metalwork Techniques – Important Intangible Cultural Property Transmission Project “Transmitting Skills”

Shakudo, Blackened Copper, Discoloration Coloring – Wabi Colors Created by Chemical Reactions

Metal jigane also dramatically changes expression through chemical treatment after processing, increasing depth as art. Shakudo involves heating copper material to around 1040°C and rapidly cooling in borax solution to create a vivid red-orange oxide film. This is an advanced process with difficult oxidation speed and finishing temperature control, with high failure rates. Blackened copper (kokudo) creates deep black colors by adding trace amounts of arsenic to copper alloys or through controlled heating and oxygen processes.

Additionally, discoloration coloring forms natural irregularities and deep textures through copper surface oxide films and heat treatment, creating “wabi” by intentionally allowing natural oxidation of materials that normally avoid rusting. By utilizing these chemical processes, jigane itself is elevated from mere material to an essential element for “visual appeal” in craft works.

Through these three major processes—forging and casting for shaping, metal engraving for patterns, and chemical coloring for wabi—jigane transforms from simple material to craftsmanship imbued with artistic soul. There exists a world where not just visual beauty, but materials and techniques resonate together.

How Jigane is Used in Representative Craft Works

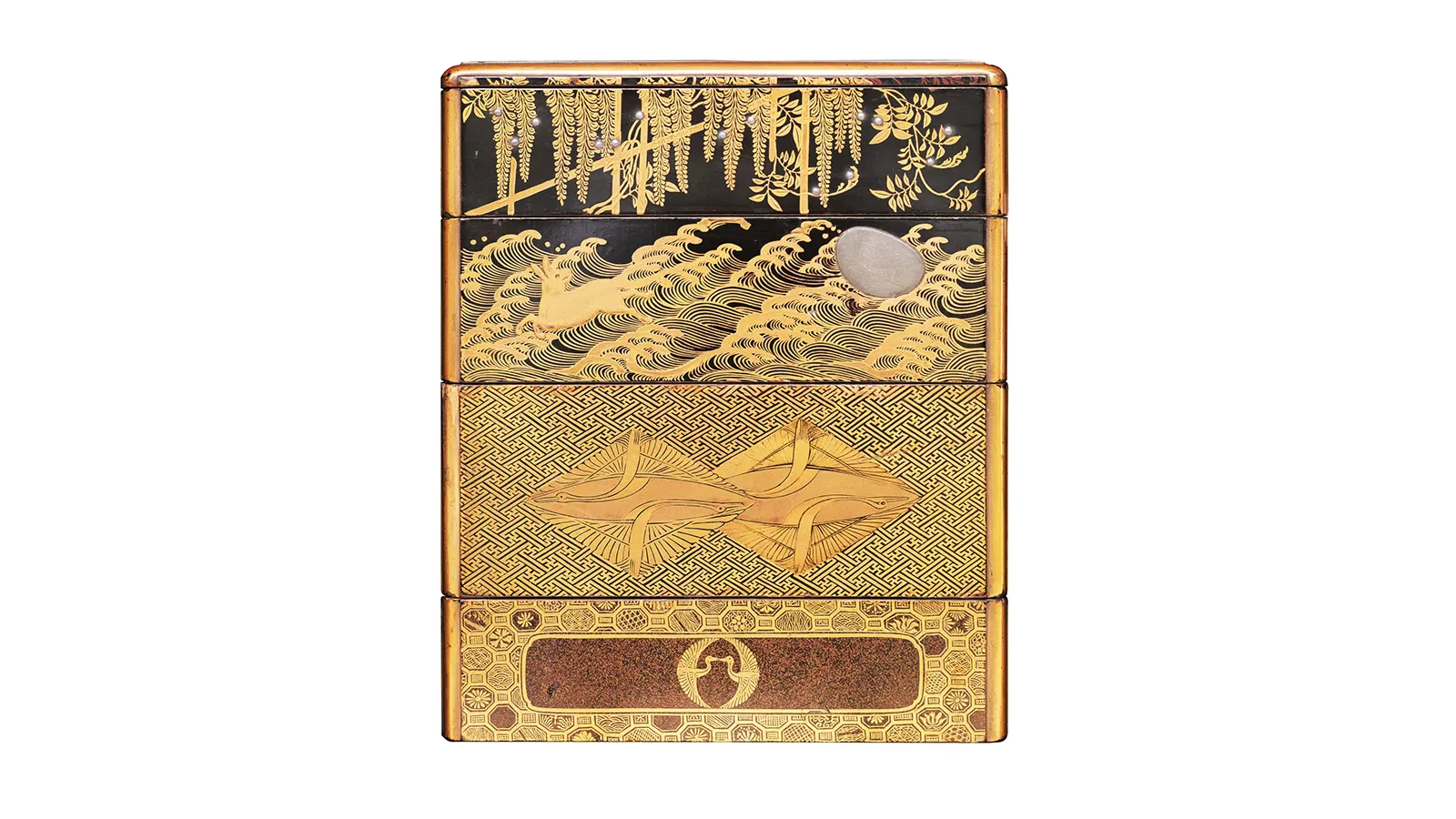

Japanese traditional crafts have greatly expanded their expressive range precisely because of metal materials called “jigane.” Sword fittings, inlay, cloisonné, ornamental metalwork, maki-e—all of these are craft works where advanced techniques have crystallized using jigane as a foundation, with their beauty born from the fusion of material properties and craftsman skills.

Below, let’s examine in detail how jigane is utilized in each representative craft work.

Sword Fittings

Sword fittings refer to decorations applied to sword sheaths and guards (tsuba), centered on inlay techniques applied to iron base metal. Inlay is the technique of creating raised patterns by fitting gold, silver, and copper into carved iron base.

“Metalwork inlay” involving carving patterns with chisels, hammering in gold leaf, and carefully pressing with hammers is work where master craftsmanship shines. For example, inlay decoration on sword guards realistically and three-dimensionally expresses dragons and flowers and birds, with the contrasting beauty of iron’s blackness and gold-silver brilliance.

This technique, which matured from the Muromachi to Edo periods and was praised overseas after Meiji, represents advanced craftsmanship that could be called “iron base art,” beautifully layering different materials on jigane.

Kyoto Inlay and Kaga Inlay

Kyoto inlay and Kaga inlay are artistic crafts that expanded decorative techniques derived from sword fittings into interior decoration, tea ceremony utensils, and tea containers. Kyoto inlay often features fine line inlay, expressing delicate worldviews by decorating iron base with silver wire in detailed flower and bird designs or geometric patterns.

Kaga inlay is inlay technique transmitted in Kanazawa, characterized by gorgeous beauty that merged with maki-e techniques and extensively used gold and silver powder and leaf. The combination of heaviness from embedding precious metals in iron base and gold luster creates luxury crafts ideal for tea ceremonies and gifts. Iron as jigane remains the foundation, but the addition of noble light creates decoration symbolizing the regional cultures of Kyoto and Kaga.

Cloisonné

Cloisonné is a technique where glass-like glaze is fired onto copper or copper alloy molds (jigane), with metal jigane serving as the foundation supporting the glaze. The color tones and heat resistance of copper base make the transparent to opaque coloration of glass-like materials stand out beautifully.

Various colors like blue, red, and green appear depending on glaze thickness and firing temperature, but this beauty is created by the copper base’s color tones and shadows showing through from behind. Without copper base, glass would be fragile and lose its translucency and color depth. Cloisonné can be said to be a craft that achieves artistic completeness through the cooperative relationship between jigane and glaze.

Ornamental Metalwork

Ornamental metalwork (kazari kanagu) is decorative craftsmanship used in temple and shrine architecture door handles and decorative fittings, and Buddhist altar ornamental fittings. Silver and gold plating is applied to copper or brass base as jigane, with the characteristic openwork carving and pattern composition unique to ornamental metalwork.

These are finished by ornamental craftsmen carving patterns with chisels and finally applying thin gold and silver layers, highlighting the dignity and solemnity of architectural beauty. The layering of multiple metal layers creates decoration that reflects religious mysticism through light reflected indoors. While jigane serves as the vessel, it transforms into sacred crafts that color pure spaces through plating and chisel carving.

Maki-e Base Metal Powder

Maki-e is representative Japanese craftsmanship that draws patterns on lacquerware with gold and silver powder, where metal powder called jigane is an important material. It’s characterized by diverse expressions including mother-of-pearl techniques and togidashi maki-e that sprinkle gold and silver powder on lacquer-adhered surfaces, further fixing while polishing.

Gold powder is processed into powder form as jigane and has high adhesion to lacquer, gaining depth that increases brilliance with each polishing. Silver powder versions offer subdued luster while gold powder provides gorgeousness, valued for decorating tea utensils, document boxes, Buddhist implements, and tea shelves. Maki-e is truly comprehensive craft beauty born from the collaboration of “metal jigane” and “lacquer.”

Common to these representative crafts is that jigane functions as the foundation supporting the three elements of “form,” “decoration,” and “color” that jigane provides to works. Jigane is not merely material, but can be said to be like a “stage setting” that supports the value and beauty of craft techniques.

Care and Preservation Techniques for Long-lasting Appreciation

Beautiful metalwork can maintain its brilliance for a long time by understanding the properties of each material and performing appropriate storage and care. Here we’ll explain in detail rust and discoloration countermeasures according to major materials like gold, silver, copper, and iron, how to select and use care products recommended by professionals, and checkpoint considerations when requesting repairs and re-plating.

Gold, Silver, Copper, Iron – Material-Specific Rust and Discoloration Countermeasures

Gold (especially 24K) has high stability and rarely rusts, but alloys like 18K and 10K may experience discoloration (dulling). This results from reactions with sweat and skin components, and oxidation of alloying metals, preventable by lightly wiping with a soft cloth after use.

Silver easily sulfurizes in air, causing blackening. This can be prevented by dry wiping after use and storing in light-blocking cases. Commercial silver polishing cloths and light cleaning with neutral detergent are also effective.

Copper and brass easily develop verdigris from moisture and acidic components, so dry wiping after use and applying wax every few months is recommended. When verdigris occurs, treatment with vinegar and salt mixture or baking soda is also effective.

Iron products require maintaining dry conditions; when wet, immediately dry wipe and store in low-humidity locations.

Professional-Recommended Cloth and Wax Selection and Usage

Suitable for daily care of gold and silver products are “jewelry cloths” and “eyeglass cloths” that contain no abrasives and have fine fibers. Simply wiping away sweat and dirt has significant effects on daily beauty maintenance.

For copper products, polish the surface with a cloth lightly soaked in metal wax every few months, finishing with dry wiping to increase luster and prevent discoloration. After using wax, be careful not to leave cloth fibers or dust.

For decorative items with delicate chisel carving or intricate ornamentation like ornamental metalwork and maki-e, cloths containing abrasives may scratch surfaces, so we recommend limiting care to light wiping with soft, dry cloths.

Checkpoint Considerations When Requesting Repairs and Re-plating

When rust or discoloration has progressed and self-treatment is difficult, consult professional contractors. Checkpoint considerations when making requests include:

- Plating type and condition

- Detailed estimates and treatment content

- Material damage prevention

- Response and warranties

Through such considerations, you can maintain the beautiful condition of precious jigane crafts for a long time without compromising their value. Using jigane crafts requires consistent management from daily care to specialized maintenance and preservation, based on understanding material characteristics. By continuing proper care and preservation methods, the beauty of jigane will continue to shine across generations.

Conclusion

Jigane in the world of traditional crafts is not merely “metal material,” but the very foundation that supports craftsmanship and expression. In diverse fields including sword fittings, inlay, cloisonné, ornamental metalwork, and maki-e, the characteristics of each jigane have determined the direction of techniques and beauty.

Additionally, care and preservation methods vary greatly depending on metal differences like gold, silver, copper, and iron. Deeply understanding jigane and handling it correctly is the first step toward loving and passing down crafts for generations. When encountering crafts, try contemplating not just surface decorations, but the power and background of the “jigane” material beneath. This should be the key to approaching the essence of Japanese craftsmanship.